The Ancient Human Being And Civilizations

It is impossible to say that South Indians exhibit any distinct racial traits. They are a collection of several physical kinds, most obviously the result of a blending of numerous strains in immemorial antiquity. Modern attempts to separate these strains are subjective judgments based on the evaluation of enigmatic and complex evidence along several lines. Therefore, there is little room for certain statements of a categorical kind given the topic of this chapter.

There are three pieces of evidence that speak to the ancient period‘s race and cultural issues. First, there is the real arrangement of physical traits among the nation’s population now, which, when carefully compared to traits shared by citizens elsewhere, may provide hints about the earliest migrations and origins of peoples.

The distribution of language groupings and their relationships with one another come in second. Although it is now widely accepted that there is no clear connection between language and race, sound grammatical evidence can be extremely valuable when studying cultural history.

When did humans first settle in South India

Analyzing the ancient stone tools and animal fossils discovered in the terraces of mountain ranges like the Siwaliks and river basins like the Godavari, The oldest known human presence in these areas dates back about 300,000 years, but for a considerable amount of time, the man only able to gather food from the environment rather than cultivate it to meet his needs. Simple hand axes and cleavers served as his only tools.

It is thought that the Sohan industry, which displays Levallois flake facies, is older than Kurnool and Nagarjunakonda example hand-axe industries, and exhibits pebble tool facies. It also appears likely that the former had more force in spreading across a wider area compared to the latter.

Paleolithic Stage

Early or Lower and Later or Upper Paleolithic are the two main divisions of the Paleolithic Stage. The existence of an Upper Paleolithic Stage in India is uncertain. In contrast, Seshadri emerges from the microlithic sectors of South India from a fictitious Levalloisian flake industry, which marginalizes the Upper Paleolithic as from a series of the Stone Stage cultures of India. Movius claims that the evolved Sohan’s presence suggests the Upper Paleolithic’s existence. This question might be clarified by more investigation, analysis of the Teri industries along the southeast coast, and Bruce Foote’s discoveries in the Kurnool caves.

While delicate blades knocked off by force peeling or with the use of a punch make up the majority of Upper Paleolithic tools in Europe, no such well-defined collection of tools is visible elsewhere in India.

A substantial collection of blades, blade-points, scrapers, borers, and occasionally arrows in fine-grained raw material like chalcedony, agate, jasper, and chert were discovered at several factory sites during S. R. Rao’s recent investigation of the stone walls caves and rock formations of Itar Pahar in the Rewa district of Madhya Pradesh. These tools are similar in appearance and purpose to those discovered in Maharashtra, The discoverers have given the new industry a number of names, including “Newasian,” “Series II,” “Middle Paleolithic,” and others.

Archaeologists finally decided to refer to it as the Middle Stone Age. The title “Middle Paleolithic” cannot be given to it because there is no definitive proof of the Upper Paleolithic Stage in India, distinguishing it from the paleolithic industry of the Beginning Stone Age on just one extreme and also the microliths of Late Paleolithic Civilizations that preceded it. On riverbeds and in rock shelters, where they might find the raw materials for tools, humans of the Middle Stone Age lived.

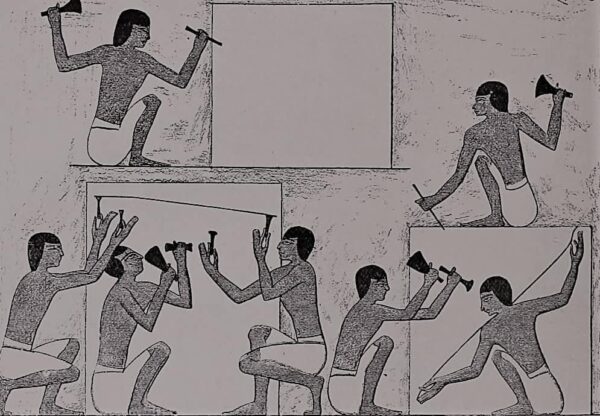

Occupations of the People

According to the evidence from Langhnaj, the people who used microliths lived on elevated sand dunes that overlooked flood lakes. The beaches originated during the preceding dry phase when the environment was wetter than it is now.

The main sources of income for the populace were hunting and fishing. People hunted, fished, and dissected animals using blades, burins, and points either individually or as part of composite tools. They consumed cattle, nilgai, deer, rhinoceros, mongoose, pigs, mice, and fish as food. The human skeleton found in Langhnaj has long, thin legs, which may have been to a hunter-fisher group. The dead were typically laid to rest in a severely flexed position facing north to south.

They resemble the Hamitic people of Egypt in terms of their physical characteristics, including their average height, long head, and slightly protruding lower lip. They were aware of pottery, but there is no proof that grains were ever used, even if they were wild-collected. The Late Stone Age is regarded as the era of the microlithic industries.

It is interesting to note that hard stone celts are related to microliths. A meticulously planned excavation at Brahmagiri in Mysore State has demonstrated this. The cultural continuity at this location, which ranges from polished stone axe culture to early historic cultures, is noteworthy. More detailed analysis is required to determine if there was not a gap in India’s consistency from the Paleolithic and through the so-called Mesolithic to the Neolithic.

The Mesolithic and Neolithic periods coexisted in Europe and abroad, with the Mesolithic giving way to the latter as knowledge of both animals and plants, as well as the technique of grinding and polishing stone implements, spread. The Neolithic’s major move from food collecting to food production took a long time. Microlithic sickle blades with that odd sheen from cutting and plants were found in Palestine affixed on bone handles.

Reconstruct the Neolithic Complex

It is quite challenging to rebuild the Neolithic complex in India. Zeuner has rightfully drawn attention to this issue. For the domestication of plants from our sites, little evidence is currently available. To elucidate the issue, skeletal material should be examined with the goal of separating wild species from domesticated ones.

But a lot of the so-called Neolithic sites in Bellary, Mysore, “Hyderabad,” and other areas of the Deccan produce polished stone axes, adzes, and chisels. The sites and communities of these people are located close to the trap dykes since that is where the materials for their tools were obtained. North Mysore’s Sanganakallu, Maski, and Brahmagiri, South Mysore’s T. Narsipur, Andhra’s Utnur, Piklihal, and Nagarjunakonda, and Kashmir’s Burzahom are just a few of the notable places in the state.

In addition to using Neolithic celts and microliths, the creators of this culture also had some understanding of dealing with copper and bronze, albeit to a limited extent. The study of this culture’s pottery at Brahmagiri and Sanganakallu is extremely valuable to those researching India’s prehistoric civilizations. ‘True Neolithic’ by Subba Rao, Sanganakallu has produced evidence of recent stone axes, a beautiful microlithic industrial, and pale grey pottery ware that is clearly older than Brahmagiri but appears to belong to the same culture complex.

Important Evidence About the habitation

Burzahom in Kashmir provides the most significant information on Neolithic human residence in the northwest. Neolithic habitation was divided into two distinct periods by Khazanchi. The era I habitation pits featured landing steps and were wide at the bottom and small at the top. Given that the steps only extended a portion of the way down, ladders may have occasionally been employed.

The walls were mud-plastered and the floor was level. Hearths and storage pits at ground level serve as evidence that the pit dwellers spent sunny days outside. The trenches were occasionally covered with perishable construction. Period II saw the pits filled and put to use as floors.

The post holes show that perishing-material superstructures have been built. In eras, I and II, dagger points, awls, chisels, needles, and harpoons made of bone and antler were observed in addition to polished axes, harvesters, polishers, pounders, and maceheads made of stone. In era III, an obtrusive mega-lithic culture replaced the neolithic one.

While the Neolithic sediments in Burzahom have been dated to 1700 B.C., those in Utnur have a 2000 B.C. Carbon-14 date. Based on this, it should be assumed that the Brahmagiri Stone Axe Culture predates 1000 B.C. Additionally, it is unquestionable that the Neolithic people interacted with the northern Deccan’s Chalcolithic inhabitants after Harappan.